Liszt and Jasmin

By 1830 there was no more evidence[1] of Caroline in Liszt’s life. More mature romances with admirers and students followed. Well-known affairs were those with Charlotte Laborie (introduced to him as a potential marriage candidate by a friend of his mother), Countess Adèle de Laprunarède (with whom he spent a romantic winter at Château Marlioz, near Aix-les-Bains) and another student, the seventeen year old ‘girl next-door’ at rue Montholon: Vera-Euphémie Didier[2].

It was at a party in Chopin’s apartment in early 1833 which Liszt attended with Berlioz that he fell in love with Countess Marie d’Agoult. It resulted in a relationship that would last more than ten years. They had met on earlier occasions — at a concert with the Marquise Le Vayer — but for Liszt the spark of love only ignited in 1833. Being of noble descent, Marie d’Agoult had less of a problem regarding the moral side of the aristocracy than Count Pierre de Saint-Cricq. She divorced her husband in August 1835 and joined Liszt on his famous Années de Pèlerinage travels through Europe. Their daughter Blandine was born in December 1835 in Geneva.

It was through the writer Marie d’Agoult (pen name Daniel Stern) and her many aristocratic connections that Liszt further expanded his social and cultural network. In November 1834 he met the unorthodox novelist Baroness Dudevant, better known by her pen name George Sand, whom he subsequently introduced to Chopin.

Many of Liszt’s new friends such as Balzac, Chateaubriand, Heine, Hugo, Lamartine, Musset, Sainte-Beuve, Sand, and Vigny wrote articles for an influential literary journal that started in 1829: Revue des Deux Mondes. This bi-monthly journal contained articles on contemporary art and travel, music reviews, and political opinions.

Liszt’s name not only showed up frequently in reviews, but also as the author[3] of articles and letters (many of them written by Marie d’Agoult in Liszt’s name). The Revue des Deux Mondes (together with the journal La Revue et Gazette Musicale de Paris) became part of his standard reading list.

It must have been either through the Revue des Deux Mondes, via one of the Parisian réunions d’artistes, or through his friendships with Charles Sainte-Beuve, George Sand, Alfred de Musset, or Alphonse de Lamartine, that Liszt was introduced to the poetry of the barber-poet Jasmin.

The poet and the composer

Jacques Boé Jasmin [4] (March 6, 1798 – October 5, 1864) was born in Agen (North-West of Toulouse) on the Garonne river. He is considered as having been one of the key poets of his time. Some compared him with Dante. The literary critic Sainte-Beuve wrote in 1851: “If France possessed ten poets like Jasmin, ten poets of his influence, she would not have to fear revolutions.” Jasmin’s real name was Jacques Boé, Jasmin being a sobriquet applied to members of his family for three generations.

Born into a poor family and trained as a barber and hairdresser Jasmin had a remarkable talent for recitation and composing verses. He was already in his late twenties when Charles Nodier[5], an author and literary critic, came upon him by chance in his barber shop in 1832, where he tried to intervene in a noisy quarrel between Jasmin and his wife. When Nodier noticed Jasmin’s poetry he proclaimed him to the world as a new Lamartine or a new Victor Hugo and found him a publisher for his poems.

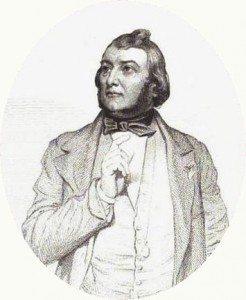

Jacques Boé Jasmin (est. 1840)

Jasmin wrote his poems in the local patois (languedocien d’Agen, similar to Gascon) which stems from the Occitan language covering the South-West of France and Pyrenees mountains. Jasmin’s first poems were written on curl-papers that he used to wind the hair of his female customers. In French, these are called Papillotes. Thus, his first and subsequent bundles of poems were named Papillotes[6] (Papillôtos in patois).

Jasmin’s first poems were published in 1825 and received excellent reviews in his home town Agen, as well as in Toulouse and Bordeaux. His oratorical eloquence meant that he was soon requested to recite his poems before large audiences in these cities. A unique aspect of the poet Jasmin was that he did not confine himself to the lyrics of his poems; He often also wrote, and sang, the musical song accompaniments to his poems. The first bundled volume of Papillotes was published in 1835 and was received with enthusiasm not only in Toulouse and Bordeaux, but also in Paris[7].

The Revue des Deux Mondes[8] of April 1837 contained an extensive and favourable review of Papillotes by Sainte-Beuve. The fifteen-page article directly followed the third section of the new novel Mauprat by George Sand and was followed by a musical review of Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, the Ouverture of which was transcribed and published by Liszt a year later. The same edition of the Revue contains a detailed description of the 1837 Salon, the world’s most important (bi) annual art exhibition in Paris. The Salon contained a masterpiece Christus Consolator by another Liszt friend, the Dutch/French painter Ary Scheffer, as well as portraits of Liszt and Sand by Scheffer.

Given Liszt’s close friendships with Sainte-Beuve (on whose book of poetry, published in 1830, he composed his series of Consolations) and George Sand as well as his general interest in music and poetry, I’m sure he cannot have overlooked this journal and the article about Jasmin.

Charles Sainte-Beuve included his review of Jasmin in his book Critiques et portraits littéraires[9] in 1839, which must certainly have been read by the voracious reader Liszt, who hosted Sainte-Beuve in Rome in June for several weeks that same year. Last but not least, Las Papillôtos was in George Sand’s library at Nohant, and in the spring of 1837 Liszt and d’Agoult were staying with her there. George Sand’s novel La Petite Fadette is said to have been suggested by the works of Jasmin[10].

Jasmin’s Franconnette

Liszt’s Faribolo Pastour composition was derived from Jasmin’s longest and most ambitious poem: Franconnette (Françouneto in patois). Jasmin completed it in 1840 and dedicated it to the city of Toulouse where it was an immediate success [11]. The Revue des Deux Mondes presented the poem in 1842, with a review by Léonce de Lavergne [12]. Jasmin’s second volume of Papillotes was published in that same year [13].

The poem Franconnette depicts the love of a beautiful young girl for a young man at the village of Agen in the 16th century. “Her beauty made many a maiden angry, made many a man sigh, for the latter all contemplated her and adored her as the priest adores the cross.” The father of the young girl was a Huguenot banished after the Huguenot – Catholic wars and thus Franconnette was considered an unfit person for marriage. According to a sorcerer, her father had sold her soul to the devil. Nevertheless, two young men, one of them a poor blacksmith called Pascal and the other a handsome young soldier with bright uniform called Marcel, fell in love with the girl. The young blacksmith Pascal considered himself unfit to court her. Franconnette enjoyed the admiration of Marcel and several other young men and flirted with them at a dance festival.

“If the prettiest were always the most sensible,” states Jasmin in one of his notes to the poem, “how much my Franconnette might have accomplished” but instead of this, she flitted from place to place, idle and gay, jesting, singing, dancing, and, as usual, bewitching all.

One of Pascal’s friends, Thomas, helped him by singing a song that Pascal had composed for her. The song was about a “siren with a heart of ice”. It showed Franconnette her cold behaviour towards Pascal and convinced her that the poor blacksmith was her true love. On this romantic note, the poem had a happy ending.

Following the article in the Revue des Deux Mondes, Jasmin received many invitations to recite his poems in Paris and eventually, reluctantly, agreed to travel there in 1842. He stayed in Paris during the month of May, meeting famous authors such as Chateaubriand whom he worshipped (as Liszt did), and was invited to recite his work at famous salons[14] and before the Academie Francaise (which included Alphonse de Lamartine, another friend of Liszt).

Jasmin’s first recitation was at the salon of writer and historian Auguste Thierry (in the presence of Thierry’s close friend Princess Cristina di Belgiojoso). He recited Françouneto and also sang the song Serèno al cò de glas on this occasion. It was referred to as a “divine love song”. Following this success, every salon in town demanded Jasmin’s presence.

The culmination of his trip was a banquet in his honour given by the barbers of Paris (after all, Jasmin was a chevalier de rasoir – Knight of the razor) and also a visit to the royal family at the palace in Neuilly on May 24th where he recited for King Louis-Philippe. Given their many mutual friends and interests it was only a matter of time before these two national superstars Jasmin and Liszt would meet. During Jasmin’s visit to Paris, however, Liszt was on a concert tour[15] in Berlin and East Prussia.

Following his success in Paris, Jasmin started a concert tour in the second half of 1842 with a professional singer and a harpist, to places like Montouban, Nîmes, Albi, Pau, Toulouse, Avignon and Marseille. It was quite similar to Liszt’s tour in 1844; except for the fact that Jasmin’s recitations were given to thousands of people in the main halls and squares, while Liszt’s piano music was limited to the concert halls and salons. Like Liszt, Jasmin was a charitable person. He never accepted money for his recitations and donated any gifts to the poor.

At that time, where Liszt was referred to as a phenomenon in every discussion concerning music, Jasmin was equally revered in places where poetry was talked about. The private and public Salons in Paris engaged them both. Liszt probably became acquainted with the poem Franconnette in the second half of 1842, either from the publication at the Revue de Deux Mondes, from a friend e.g. Lamartine, George Sand, or Thierry, and/or via a recitation at one of the broadly advertised artists gatherings in Paris that he frequented.

Franconnette must have brought back Liszt’s suppressed memories of his adolescent love affair with Countess Caroline de Saint-Cricq where he had found himself unfit for marriage. The presence of other marriage candidates: wealthy, older and more experienced in the art of courting, and Franconnette’s eagerness to dance with them would also have been noted.

Another element in the poem that must have struck a chord with Liszt is the Huguenot association. Liszt’s Grande fantaisie sur les themes de l’opera Les Huguenots, based on Meyerbeer’s opera was composed and revised in the period 1836 – 1842. This opera tells a similar story about the Catholic Valentine and her Huguenot lover Raoul.

Liszt used the song Serèno al cò de glas – Siren with a heart of ice for his 1844 Faribolo Pastour composition, and it is this song and its dedication to Caroline that provides us with new clues about his adolescent love affair.

The poem Franconnette might never have materialized as a composition if it weren’t for the fact that Liszt met its author, Jasmin, and his former love Caroline during his concert tour to the South in the second half of 1844.

Next: 1844 Concert Tour

[1][↑] Liszt was never far away from the Saint-Cricq family in Paris. When he moved from Rue Montholon 7 to Rue de Provence 61 in 1831, the house at rue de Provence 67, was inhabited by Caroline’s brother Jules de Saint-Cricq. Shortly before her marriage, Caroline lived at Rue de Provence 6.The press contained regular articles about this renowned Minister and more than once, Liszt met with aristocrats related to the Saint-Cricq family, such as Ambassador and Foreign Minister Edouard Drouyn de Lhuys.

[2][↑] Pierre-Antoine Huré and Claude Knepper, Liszt en son temps: Documents choisis, présentés et annotés, Paris, Hachette, 1987, p. 67.

[3][↑] E.g. Revue des Deux Mondes: A Liszt, Sur Lavater et sur une maison déserte, Sept 1, 1835; Lettre de M. F. Liszt au directeur de la Revue, Nov 15, 1840; Chopin et Liszt, April 1, 1842 (p. 162); Publications musicales en France, en Russie et en Allemagne, MM. F. Liszt, Th. Wagner, W. de Lenz, August 15, 1852; La musique des Bohémiens, de M. Franz Liszt, August 1, 1859.

[4][↑] Three fairly contemporary references:

- Samuel Smiles, Jasmin: Barber, Poet, Philanthropist, London, Murray 1891. Most of the quotes in this essay on Jasmin were derived from this book;

- The Westminster and Foreign Quarterly Review, London, Luxford; January 1850;

- Raoul Vèze, Jacques Jasmin: sa vie. Conference 22 février 1901 à la Société Lot-et-Garonnaise de Paris, 1901.

[5][↑] Charles Nodier was key to the French world of literature. He became a member of the French Academy in 1833. His work was often quoted, i.e. by Hector Berlioz who compared Frederick Chopin with the soft gentle and gallant elf from Nodier’s book Trilby, or the Elf from Argail (published by Nodier in 1822).

[6][↑] Jacques Jasmin, Las Papillôtos, 1825 – 1835, Tome I, Agen, Firmin Didot, 1835.

[7][↑] According to Nodier, even Homer couldn’t have written better verses. Upon hearing and reading the poetry from Jasmin, writer Paul de Musset undertook the long journey from Paris to Agen in 1836 to meet this new star. The cultural world was small in those days: Paul was acquainted with Liszt through the relationship that his brother, the poet Alfred de Musset, had had with George Sand until 1835.

[8][↑] Sainte-Beuve, “Poètes et Romanciers Modernes de la France, XXII: Jasmin”. Revue des Deux Mondes, Tome Dixième, Quatrième série, Paris, 1837, p. 389.

[9][↑] C.-A. Sainte-Beuve, Critiques et Portraits Littéraires, Vol. IV, Paris, Bonnaire / Renduel, 1839, p. 428.

[10][↑] Preface by Jean Courrier to George Sand, La Petite Fadette, 2007, Romagnat, ed. De Borée.

[11][↑] Jasmin recited Françouneto for an audience of 1500 at the Museum Hall in 1840. Some towns were carpeted with flower petals in honor of his arrival. Besides in Toulouse and his hometown Agen he recited the work at Pau for a large audience. Jasmin’s fame quickly travelled outside France to England and the U.S.A. His poems have been translated by the legendary American poet Henry Longfellow. For reasons of clarity I have used more literal translations of Jasmin’s poems in this essay rather than Longfellow’s poetic translations.

[12][↑] Léon Lavergne, Revue des Deux Mondes, Quatrième serie, Tome XXIX, Paris, January 1842, p. 282. The same edition contains articles by Charles Sainte-Beuve and a poem Alfred de Musset, so also this publication could not have been overlooked by Liszt.

[13][↑] Jacques Jasmin, Las Papillôtos 1835 – 1842, Tome II, Agen, Firmin Didot, 1842, with Françouneto on p. 137.

[14][↑] Martial Delpit, “Jasmin a Paris”, Annales Agricoles et Littéraires de la Dordogne, Perigeux, Dupont, 1842, p. 191.

[15][↑] Michael Saffle, Liszt in Germany 1840 – 1845, Franz Liszt Studies Series #2, American Liszt Society, 1994, p. 155.