Liszt in London, 1886

Madame Mary King Waddington, an American author who lived with her husband, the French statesman William Henry Waddington for several years in Paris just after the French-German war, published her experiences in the book: “My First Years as Frenchwoman, 1876-1879”, published in London by Smith, Elder & Co, 1914.

She describes a clever strategy to lure the old master Franz Liszt to play the piano. Her anecdote starts early in 1878 when she meets Liszt for the first time. Mary Waddington and her husband moved to England in 1883 when William became French ambassador to the Court of St James. The second part of her story happened in the first weeks of April 1886 when Liszt paid his last visit to England. Key person to get Liszt to play is the German ambassador Count Paul von Hatzfeldt. The Hatzfeldt family were good friends of Liszt. He attended the première of Tristan with Princess Marie von Hatzfeldt in Bayreuth on July 25, 1886, six days before his death.

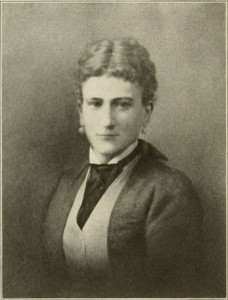

Madame Waddington, 1878

“We sometimes had informal music in my little blue salon. Baron de Zuylen, Dutch minister, was an excellent musician, also Comte de Beust, the Austrian ambassador. He was a composer. I remember his playing me one day a wedding march he had composed for the marriage of one of the archdukes. It was very descriptive, with bells, cannon, hurrahs, and a nuptial hymn- rather difficult to render on a piano—-but there was a certain amount of imagination in the compo-sition.

The two came often with me to the Conservatoire. Comte de Beust brought Liszt to me one day. I wanted so much to see that complex character, made up of enthusiasms of all kinds, patriotic, religious, musical. He was dressed in the ordinary black priestly garb, looked like an ascetic with pale, thin face, which lighted up very much when discussing any subject that interested him.

He didn’t say a word about music, either then or on a subsequent occasion when I lunched with him at the house of a great friend and admirer, who was a beautiful musician. I hoped he would play after luncheon. He was a very old man, and played rarely in those days, but one would have liked to hear him. Madame M. thought he would perhaps for her, if the party were not too large, and the guests “sympathetic” to him. I have heard so many artists say it made all the difference to them when they felt the public was with them — if there were one unsympathetic or criticising face in the mass of people, it was the only face they could distinguish, and it affected them very much.

The piano was engagingly open and music littered about, but he apparently didn’t see it. He talked politics, and a good deal about pictures with some artists who were present.”

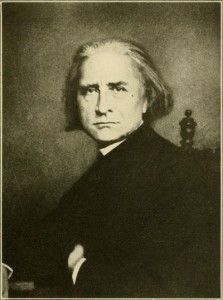

Franz Liszt, 1867

“I did hear him play many years later in London.

We were again lunching together, at the house of a mutual friend, who was not at all musical. There wasn’t even a piano in the house, but she had one brought in for the occasion. When I arrived rather early, the day of the party, I found the mistress of the house, aided by Count Hatzfeldt, then German ambassador to England, busily engaged in transforming her drawing-room.

The grand piano, which had been standing well out toward the middle of the room, open, with music on it (I dare say some of Liszt’s own — but I didn’t have time to examine), was being pushed back into a corner, all the music hidden away, and the instrument covered with photographs, vases of flowers, statuettes, heavy books, all the things one doesn’t habitually put on pianos.

I was quite puzzled, but Hatzfeldt, who was a great friend of Liszt’s and knew all his peculiarities, when consulted by Madame A. as to what she could do to induce Liszt to play, had answered: “Begin by putting the piano in the furthest, darkest corner of the room, and put all sorts of heavy things on it. Then he won’t think you have asked him in the hope of hearing him play, and perhaps we can persuade him.”

The arrangements were just finished as the rest of the company arrived. We were not a large party, and the talk was pleasant enough. Liszt looked much older, so colourless, his skin like ivory, but he seemed just as animated and interested in everything. After luncheon, when they were smoking (all of us together, no one went into the smoking-room), he and Hatzfeldt began talking about the Empire and the beautiful fétes at Compiègne, where anybody of any distinction in any branch of art or literature was invited.

Hatzfeldt led the conversation to some evenings when Strauss played his Waltzes with an entrain, a sentiment that no one else has ever attained, and to Offenbach and his melodies—one evening particularly when he had improvised a song for the Empress——he couldn’t quite remember it. If there were a piano-—he looked about. There was none apparently. “Oh, yes, in a corner, but so many things upon it, it was evidently never meant to be opened.”

He moved toward it, Liszt following, asking Comtesse A. if it could be opened. The things were quickly removed. Hatzfeldt sat down and played a few bars in rather a halting fashion. After a moment Liszt said: “No, no, it is not quite that.” Hatzfeldt got up. Liszt seated himself at the piano, played two or three bits of songs, or Waltzes, then, always talking to Hatzfeldt, let his fingers wander over the keys and by degrees broke into a nocturne and a wild Hungarian march.

It was very curious; his fingers looked as if they were made of yellow ivory, so thin and long, and of course there wasn’t any strength or execution in his playing—it was the touch of an old man, but a master-——quite unlike anything I have ever heard.

When he got up, he said: “Oh, well, I didn’t think the old fingers had any music left in them.” We tried to thank him, but he wouldn’t listen to us, immediately talked about something else. When he had gone we complimented the ambassador on the way in which he had managed the thing.”

A detailed description of Liszt’s last time in London can be found in the The Musical Times, May 1, 1886, Vol. 27, No. 519, pp. 253-259.

You can read this article if you click on the above Musical Times link ( 2 MB).